When bacteria evolve to shrug off antibiotics, doctors usually switch drugs and hope for the best. Our framework suggests something more audacious: plan a sequence of drugs that steers evolution backward, nudging microbes toward a genotype that’s once again vulnerable.

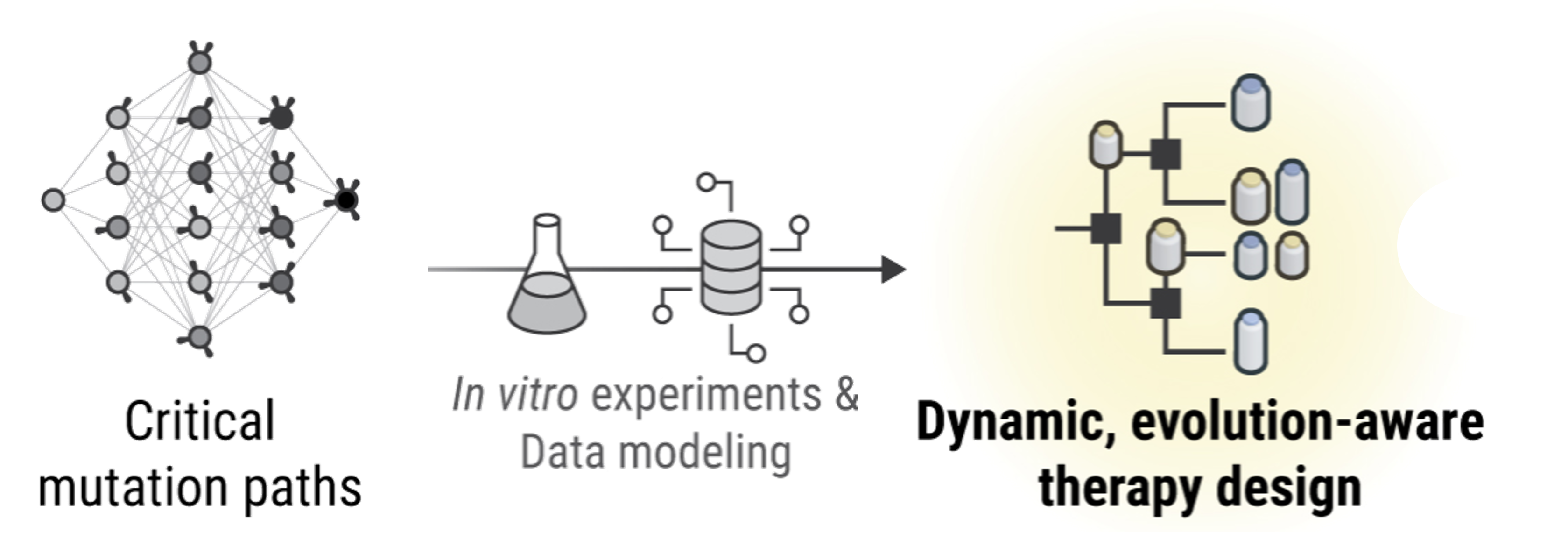

The idea starts with lab measurements of how bacterial genotypes grow under different antibiotics. From those data, we construct a genotype graph where each drug induces its own set of likely evolutionary moves. Stack those moves over time and you get a map for plotting multi-step treatment plans. Two simple rules translate growth rates into movement on the graph. In the Correlated Probability Model (CPM), the bigger a neighbor’s growth advantage, the more likely evolution flows that way. In the Equal Probability Model (EPM), all fitter neighbors are treated the same. Either way, each antibiotic corresponds to a transition matrix, the probability of hopping from one genotype to another in a single step.

With these maps in hand, we tackle two versions of the problem: static schedules commit to a fixed drug order in advance. This is tricky, NP-hard in general, so we reformulate the search as a mixed-integer linear program to find high-probability routes efficiently. Dynamic policies choose the next drug based on where evolution actually lands, a GPS that can reroute in real time. Here, dynamic programming delivers the optimal choice at each step.

Real data are noisy, so we build uncertainty into the planning. Instead of locking into a single, possibly wrong transition matrix per drug, we average over many plausible ones estimated via sample-average approximation. That yields robust schedules without blowing up the computation. What happens when you run the numbers? Across dozens of scenarios, fifteen starting genotypes, up to sixteen steps, CPM and EPM, longer plans help, and dynamic policies help even more. Static schedules steadily lift the chance of returning to the wild type, reaching roughly greater than 0.70 with CPM and greater than 0.50 with EPM by sixteen steps. Dynamic policies, however, can push success above 0.99, achieved by eleven steps under CPM and fourteen under EPM, while remaining fast to compute.

Why it matters: collateral sensitivity, the tendency for resistance to one drug to increase sensitivity to another, won’t save us automatically. But if we can chart where it exists and sequence drugs to exploit it, treatment becomes navigation, not brute force. The time machine formalizes that navigation and bakes in measurement uncertainty, offering clinicians and lab scientists a reproducible way to test smarter drug orders.

Caveats remain. The approach relies on having genotype–drug growth data, and real infections involve immune systems, pharmacokinetics, and spatial structure that lab plates can’t capture. Still, the framework is modular and the code is public, inviting new datasets, transition rules, and constraints. The big idea endures: don’t just hit bacteria harder, steer them, step by calculated step, back to where our medicines work.