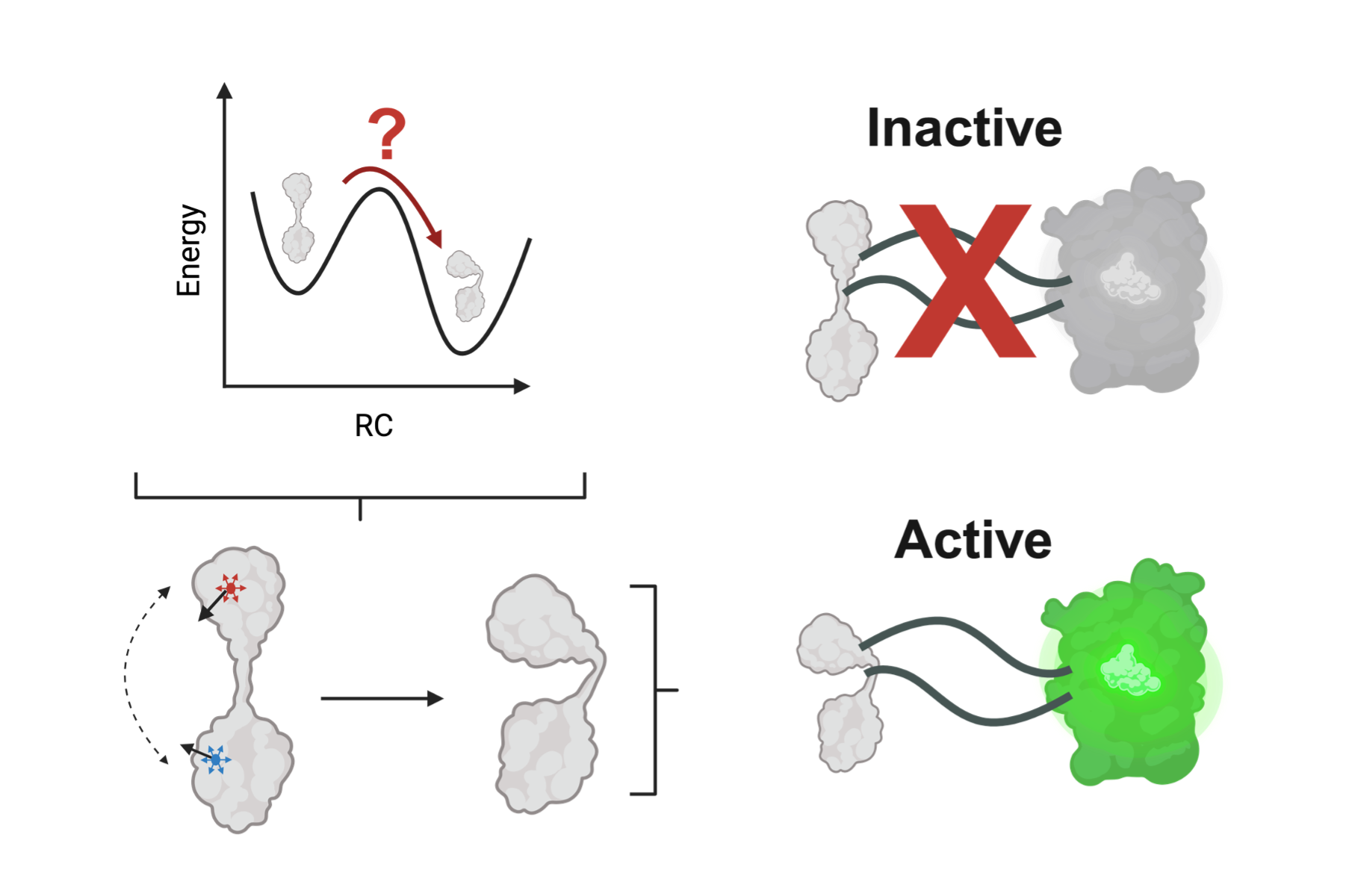

Proteins don’t just exist; they perform. They flex, breathe, and communicate, flipping between shapes that switch biological circuits on and off. Understanding where to push a protein has long been a guessing game. In biosensor design, researchers splice fluorescent reporters into sensing proteins, hoping that a ligand-binding event will ripple through the structure and light up the signal. Trial and error can work; but it’s a painfully slow way to listen to molecular whispers.

Now a physics-guided framework called Multiply Perturbed Response (MPR) offers a shortcut. Instead of probing one amino acid at a time, it asks which small combination of residues, when pushed together, most efficiently drives a protein from its inactive “apo” shape to its active “holo” form. Built on linear-response theory, MPR extends classical Perturbation Response Scanning, mapping not just single-site sensitivity but the cooperative choreography of multiple sites that is the essence of allostery.

When applied across model proteins that serve as the sensory cores of fluorescent biosensors, MPR consistently rediscovered experimentally validated “insertion neighborhoods.” They are the hot spots where mechanical signals travel cleanly from binding pocket to reporter domain. These allosteric hubs act like transmission gears, coordinating local ligand binding with global conformational motion. The analysis also revealed which regions to avoid: rigid scaffolds that mute signals or structural hinges whose disruption could cause misfolding.

The implications reach far beyond biosensing. Many enzymes and receptors are naturally allosteric, integrating cellular signals or resisting drugs by rerouting communication through alternative pathways. MPR provides a way to see those paths quantitatively. The same physics that guides fluorescent-sensor optimization could, in principle, expose the hidden relay networks that let pathogens evolve drug resistance or that govern how therapeutic molecules bias a receptor’s motion. In silico, the identified residues can even serve as collective variables that are explicit levers for steering molecular simulations or designing molecules that modulate motion rather than block binding.

Linear models can’t capture every nuance of a protein’s restless landscape. Yet MPR delivers something long missing from that landscape: a simple, interpretable atlas of the few levers most likely to move the machine; and, perhaps, to re-tune life’s most adaptable engines.